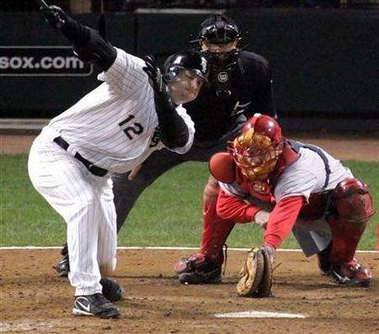

WHITE SOX PITCHER ORLANDO HERNANDEZ, AKA “EL DUQUE,” PUMPS HIS FIST IN TRIUMPH AFTER STRIKING OUT JOHNNY DAMON TO END THE 6TH INNING IN THE CHISOX 5-3 SERIES CLINCHING VICTORY OVER BOSTON

The box score and even most news reports that tell what happened in the bottom of the 6th inning of the Chicago White Sox series clinching 5-3 win against Boston give only the barest of bones about the gorgeous one-on-one struggles between White Sox pitcher Orlando Hernandez and the Bosox hitters. To flesh out what really happened and why, one must look deeper into the very soul of the game of baseball itself to discover the secret by-plays and timeless strategies of both hitters and pitchers to recognize why that sequence was so special both to baseball purists and the history of the game.

First, a little background. The White Sox had gone up 4-2 in the top of the inning thanks to a towering home run by slugger Paul Konerko, one of the few Chisox players not bewitched by Boston pitcher Tim Wakefield’s fluttering, sinking, diving and dancing knuckleball.

At times, Wakefield was damn near unhittable. The knuckleball is thrown in such a way as to negate any rotation on the ball thus not allowing the seams to cut through the air so that the ball flies straight and true toward its target. Instead, because the 60 feet six inches between the pitcher’s mound and home plate is full of currents and eddies of air, the knuckler floats like a paper airplane, diving and rising, swerving and dipping, even appearing to “flutter” up and down and back and forth until it finally arrives at home plate. The pitcher “controls” the pitch in only the grossest sense. And the poor catcher has a devil of a time trying to corral the ball.

But it’s the hitter you should be feeling sorry for. To be effective, the knuckler is usually thrown under 70 miles an hour. Given that most major league fastballs are in the 90 MPH range, the hitter is flummoxed not only by a baseball that changes direction three or four times before getting to him, but it also arrives at the plate traveling not much faster than a good little leaguers fastball. To the batter, what appears to be a slow ball coming at him as big as a pumpkin will, in the end, usually fall out of the strike zone making the batsman look silly as he swings at nothing but air.

This was Wakefield for most of the game. With the exception of a rough spot in the top of the third where the White Sox were able to string together two doubles and a single with two out for two runs, Wakefield had the Chicago hitters hogtied.

Then in the 6th, Jermaine Dye waited out Wakefield and wangled a walk. Konerko followed with his blast and that was it for the Boston pitcher. The White Sox managed to put a couple runners on, but 3 Red Sox pitchers finally got out of the inning.

That half inning lasted nearly 35 minutes which meant that White Sox pitcher Freddie Garcia had been sitting and stiffening up while his teammates were batting. The first hitter he faced in the bottom of the sixth was Manny Ramirez who promptly sent one of Freddie’s slider’s in the general direction of New Hampshire. The ball, in fact, may still be airborne as I write this. It was Ramirez second homer of the game, a titanic blast that proved why he is so much fun to watch hit even if he is on the other team. Almost as much fun to watch bat is David Ortiz who was responsible for the other Red Sox tally also via the homer.

That was it for Garcia who pitched adequately but walked 4 batters and gave up the aforementioned 3 home runs. He gave way to Damaso Marte who promptly got in trouble by giving up a single to Trot Nixon and then two successive walks to load the bases with no one out. One wonders if that is the first and only time Marte will make an appearance in the playoffs as the once unhittable pitcher has become a league punching bag.

Enter Orlando Hernandez. Last winter when the White Sox were looking for a 5th starting pitcher, General Manager Ken Williams wanted to get someone with extensive playoff experience. The fact that he got Hernandez was a stroke of genius as most baseball experts believed El Duque’s best days were behind him. The Cuban defector had a great record in the playoffs however and after a mediocre year as a starter, manager Ozzie Guillen decided to add the aging hurler to the playoff roster to give some seasoning to the young, inexperienced arms in his bullpen.

El Duque came out of the pen with his usual swagger. As St. Louis Cardinal Hall of Fame pitcher Dizzie Dean once said “It ain’t braggin’ if you can do it,” and El Duque was going to need all of his guile, his talent, and a great deal of pluck to get out of this game altering situation.

After throwing his 8 warm-up tosses, into the batter’s box steps one of the great clutch hitters of the game, Red Sox Captain Jason Varitek. Varitek hadn’t shaved for about three days and he looked like the true throwback player that he his; a scowling, menacing, hulking presence at the plate. El Duque stared at him while Varitek went through his “routine” or the rigmarole that all batters have before they get set to hit. Varitek got ready, bat poised off his shoulder, his eyes intent on Hernandez. But El Duque just kept looking at him. Varitek, not wanting to give in to El Duque’s little stratagem of trying to freeze him, kept his eye on Hernandez, his bat very still while time itself slowed and the crowd grew a little quieter. But El Duque just continued to stare at Varitek intently. Finally, the scowling slugger gave in and called for time, stepping out of the batter’s box.

Round one to El Duque.

Immediately upon his return into the hitters area, Varitek needed to get ready because Hernandez was going into his stretch. This is a veteran pitcher’s trick to keep the hitter from getting too comfortable, too familiar at the plate – especially in game situations. El Duque then reared back and fired…his “ephus” pitch. Also called a “parachute” pitch, the ball actually travels in an arc to home plate like a slow-pitch softball delivery. Hernandez pitch wasn’t a true ephus pitch but it had the desired effect. Even though it fell over the plate several inches inside, Varitek’s eyes went wide and he started talking to himself.

Round Two to the pitcher.

Varitek never had much success in his career against Hernandez, getting only 3 hits in 29 at bats. Now that El Duque had him off balance, he quickly worked the count to 1 ball and two strikes. Hernandez then delivered the perfect pitch; a high fastball, slightly inside. It was too close for Varitek to take, hoping it would be a ball and he was forced to swing at it. The result was a weak pop-up in foul ground caught by White Sox first baseman Paul Konerko for the first big out of the inning.

Round three TKO to Hernandez.

Next up was the excellent clutch hitting Tony Graffanino who had the extra incentive to redeem himself following his unforced error at second base in Game 2. Graffanino is the consummate pro and took the first two offerings by Hernandez for balls. Being up 2 balls no strikes with the bases loaded and one out is almost an automatic “hit away” situation. The pitcher absolutely has to throw a strike. Hernandez delivered and Graffanino was right “on” the pitch – his timing was right – but he only got a piece of the ball and it went back to the screen for strike one.

The next pitch was a little trickier. It was one of El Duque’s specialties – a sweeping, swerving slider that Graffanino topped into the ground in foul territory for strike two. And then, the battle was really joined as Graffinino fouled off two Hernandez rising fastballs and then watched a slider dip low and away for ball three.

This put Graffinino in the drivers seat. El Duque just had to come to him with a strike. A walk would force in a run. No one knew this better than El Duque. But over the next four pitches – all fouled off by the tenacious Graffanino – Hernandez proved that it mattered where you throw a strike. His pitches were all barely off the plate – not a true strike among them. But Graffinino didn’t want to strike out either, so with a brilliant piece of hitting and plate coverage, he got a piece of each of El Duque’s offerings, hoping that Hernandez would make a slight error and he could get the meaty part of the bat on the ball and drive it to the outfield for at the very least a sacrifice fly that would tie the score.

Finally, after 10 nerve wracking pitches, Chisox catcher A.J. Pierzynski called time and went out to discuss the matter with Hernandez. After the game, El Duque said that he told A.J. he wanted to throw a slow curve to throw Graffanino off stride. From the looks of the conversation on the mound, A.J. was probably trying to talk Hernandez out of it. In the end, Hernandez ended up throwing a slow, spinning, get-me-over curve ball that badly fooled Graffanino who was still looking for the heat. Tony G swung and popped the ball weakly to shortstop Uribe.

Second set to El Duque.

That confrontation with Graffinino was almost too beautiful to watch. It was beyond classic. It reached down and grabbed the very essence of what baseball is – a team game that is almost totally dependent on a mano a mano confrontation between a pitcher and a hitter. High salaried, spoiled players can’t ruin it. Greedy owners can’t ruin it. Even inane announcers couldn’t ruin that moment.

And it wasn’t over yet.

Up steps one of the top five hitters in the game, Red Sox center fielder Johnny Damon. Damon of the 197 regular season hits. Damon of the 75 RBI’s – an astronomical total for a leadoff hitter. Damon of the grimly determined bunch of Red Sox fatalists who never gave up and was one the heroes of the Red Sox magical run to the Championship in 2004.

More El Duque gamesmanship as he does a little mound cleaning just as Damon steps into the batters box. With his spikes, he carefully digs a little trench on the third base side of the pitcher’s rubber. His concentration on his mound maintenance is apparently total. A closeup of the pitcher however, shows a grim little smile playing at the corners of his mouth.

Following the game, Paul Konerko was asked what he thought of Hernandez. Konerko averred that El Duque had more heart than any player he had ever been around. Ozzie Guillen called Hernandez “cold blooded.” Either way, Hernandez would need all of his wits and wisdom to get past Johnny Damon and get out of the inning unscathed.

El Duque began to fire; Strike one fastball. Ball one fastball outside. Strike two on a fastball Damon couldn’t catch up to and fouled off to the left. Ball two on another fastball. Another foul on a slider. And a curve ball that broke off the plate inside took the count the 3 balls and 2 strikes once again. A rising fastball was fouled off again by Damon.

The crowd, a screaming, swaying, living , breathing thing was on its feet begging, imploring, trying to will the miracle all by themselves. The Red Sox nation never gives up. And if you didn’t get a chill listening to that crowd and watching the action and the by-play of that inning, you must be drinking formaldehyde ‘cause you’re not livin’ the way the rest of us are.

Another 3 and 2 pitch was in the offing and El Duque had a choice. Damon had been timing his fastball and was more than likely to hit it hard if he threw it over the plate. So he chose to throw is breaking ball. The pitch started over the middle of the plate but then, as Damon started his swing, the ball broke viciously downward, diving into the dirt. Too late, Damon had started his swing and couldn’t stop it before the bat had crossed home plate. No appeal to the third base ump was even necessary. Damon had struck out and he knew it.

Game, Set, Match El Duque.

The rest of the game was nerve wracking but mostly anti-climactic. Hernandez had the Red Sox eating out of his hand in the 7th and 8th inning, allowing only a Texas League single to John Olerude. And after the White Sox literally squeezed a run across in the top of the ninth giving them a two run lead, all that remained was for baby-faced Bobby Jenks to blow the Red Sox away in the ninth inning, a task that he accomplished with an alacrity that was almost like a merciful coup de grace to the Red Sox. Their gallant run was over.

For the celebrating White Sox, it was a trip back home to await the outcome of the Angels-Yankees series. And if those games have half the drama of the last two, I would suggest you get your heart medication refilled quickly. And while you’re at it, keep the Prozac handy because White Sox fans can anticipate even more nerve wracking chills and thrills during this next, longer, 7 game series.

UPDATE

The Crank ignores my Chisox clincher and gives a short, sweet, and spot-on analysis of the Yanks-Angels marathon that brought the Bronxies to the brink of elimination. While he rightly touts Torre as a great playoff manager, I questioned his use of Small in that relief situation in the fourth. While I recognize that he needed a pitcher that could have given him at least three innings, couldn’t Sturtz have filled the bill? As a former starter, Tanyon may have been more effective, being used to coming out of the pen. As it was, Sturtz came out of the bullpen to face only one batter.